Ed the Happy Clown

| Ed the Happy Clown | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

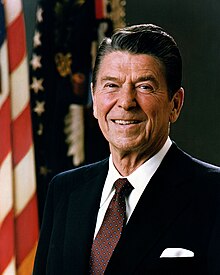

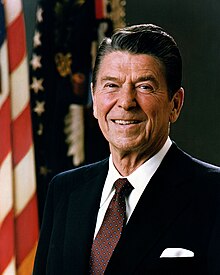

Ed the Happy Clown: the Definitive Ed Book cover (Vortex, 1992) | |||||||||||||

| Publication information | |||||||||||||

| Publisher | |||||||||||||

| First appearance | Yummy Fur minicomic #2 | ||||||||||||

| Created by | Chester Brown | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Ed the Happy Clown is a graphic novel by Canadian cartoonist Chester Brown. Its title character is a large-headed, childlike children's clown who undergoes one horrifying affliction after another. The story is a dark, humorous mix of genres and features scatological humour, sex, body horror, extreme graphic violence, and blasphemous religious imagery. Central to the plot are a man who cannot stop defecating; the head of a miniature, other-dimensional Ronald Reagan attached to the head of Ed's penis; and a female vampire who seeks revenge on her adulterous lover who had murdered her to escape his sins.

The surreal, largely improvised story began with a series of unrelated short strips that Brown went on to tie into a single narrative. Brown first serialized it in his comic book Yummy Fur, and the first, incomplete collected edition in 1989, titled Ed the Happy Clown: A Yummy Fur Book. Shortly after, Brown became unsatisfied with the direction of the serial; he brought it to an abrupt end in the eighteenth issue of Yummy Fur and turned to autobiography. A second edition titled Ed the Happy Clown: The Definitive Ed Book appeared in 1992 with an altered ending and most of the later parts of the series eliminated. The contents of this edition were re-serialized with extensive endnotes in 2005–2006 as a nine-issue Ed the Happy Clown series and collected as Ed the Happy Clown: A Graphic-Novel in 2012.

The story is seen by many critics as a highlight of the 1980s North American alternative comics scene. It has left an influence on contemporary alternative cartoonists such as Daniel Clowes, Seth, and Dave Sim, and has won a Harvey and other awards. Canadian film director Bruce McDonald has had the rights since 1991 to make an Ed film, but the project has struggled to find financial backing.

Background

[edit]Brown grew up in Châteauguay, Quebec, a Montreal suburb with a large English-speaking minority.[1] He was an introverted youth attracted to comic books from a young age. He aimed at a career drawing superhero comics, but was unsuccessful in getting work with Marvel or DC Comics after graduating from high school.[1] He moved to Toronto and discovered underground comix[2] and the small-press community.[1]

By the early 1980s Marvel and DC had come to dominate comic-book publishing in North America, and comic shops became the main places of purchase, with a clientele of dedicated comics fans. During this time, a trend towards greater ambition and expressiveness was developing on the fringes, such as Dave Sim's long Cerebus series and the avant-garde graphics magazine Raw in which the serialization of Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus appeared.[3] Brown was to find himself in the alternative comics scene that grew throughout the decade.[4]

Brown was feeling himself in a creatively stagnant period when he came across a book on Surrealism: Wallace Fowlie's The Age of Surrealism (1950).[5] The book motivated Brown to work on an improvised minicomic series which he called Yummy Fur[6] and self-published from 1983.[1]

Content

[edit]Ed suffers one indignity after another as the plot gets grimmer and more surreal. His bizarre misfortunes include having the tip of his penis replaced by the head of a miniature, talking Ronald Reagan from another universe. Ed's adventures featured encounters with penis-worshipping pygmies, flesh-eating rats, Martians, Frankenstein's monster, and other characters from traditional genre fiction. The story unfolds with a black-comedic sensibility topped with Christian symbolism. Despite his ordeals—being imprisoned for a crime he did not commit, falling in love with a vampire—Ed remains a gentle, childlike innocent, with a Candide-like optimism.[6] The story has had more than one ending[7] and is a challenge to summarize.[8]

Summary

[edit]The children's hospital Ed is about to visit burns down with all the children in it.[6] A number of apparently unrelated short gag strips appear [7] before Brown begins to tie the narrative together into one plot.[9]

Ed is imprisoned when he finds hospital janitor Chet Doodley's severed hand and the police assume Ed had taken it. In the prison, a man is unable to stop defecating and his faeces fill the jail engulfing all, including Ed. When Ed emerges he finds the head of his penis replaced with the head of a miniature Ronald Reagan from Dimension X—a world much like Ed's but whose people are tiny. Dimension X has dumped its waste into a trans-dimensional portal, which turns out to be the anus of the man who could not stop defecating. Reagan's body remains in Dimension X, and the professor who discovered the portal travels to Ed's dimension to find the head, making contact with the authorities of Ed's world.

Chet believes the loss of his hand is due to his unfaithfulness to his wife;[9] as a child his mother read Chet the story of a Saint Justin who cuts off his right hand to avoid sinning, and Chet assumes his lost hand is a like punishment from God.[10] He tries to atone for it[9] by killing his girlfriend, Josie, in the woods.[10] Penis-worshipping, rat-eating pygmy cannibals drag the bodies of both Josie and Ed into the sewers. As they are about to sever Ed's penis, Josie reanimates in time to save him. The two attempt to escape from the sewers when they are accidentally shot by a mother–daughter team of pygmy hunters. Josie dies again, and her disembodied spirit learns from the ghost of Chet's sister that she has become a vampire.[11]

The professor from Dimension X and members of the staff of the Adventures in Science TV show find Ed and the President and bring them to the TV studio. The discovery is big news, and the professor and the President make a TV appearance. When it is discovered that the people of Dimension X are homosexual or bisexual[12] the professor is put to a violent death,[11] and Ed and the body of Josie are put in confinement. The studio is invaded by the pygmies when they recognize their "Penis God" on television. Josie's spirit returns to her body, and she and Ed escape and make their way to the hospital where Chet works. Josie gets her revenge by seducing Chet and killing him before he is able to repent, thus sending him to Hell.[13]

Ed is one of a number of men secretly kidnapped to provide another, Bick Backman, with a penis transplant—a larger one to please his wife. Out of the lineup of unconscious men, Ed's penis with the President's head on it stands out and is chosen for Backman. After the operation, Mounties raid the hospital and, finding Reagan, take Backman and leave Ed, who has had a larger penis sewn on in the President's place. The hospital hands Ed over to Mrs Backman, claiming he is her husband. Though suspicious, she accepts Ed—and his newly transplanted penis.[10]

Endings

[edit]The ending that appeared in Yummy Fur has not appeared in book editions. In it, Mrs Backman takes Ed home, but her children are not convinced he is their father. After he spends some time in the house they decide "he's way better than the other one".[14] There is a resemblance between Ed and Mrs Backman, and it is revealed they were twins separated at birth. While at church, the Backman children are kidnapped by stone aliens and are saved by Frankenstein's monster, who brings them to Washington, D.C. where they find their kidnapped real father. Josie and Ed's zombie friend rescues the Backmans. Ed has his clown makeup restored and reverts to his cheerful self. When he goes to visit Josie, he learns her apartment building has burned down, and she was the only casualty. Her charred skeleton is brought out, clutching an unburnt severed hand.

The alternate ending from the 1992 and later versions drops most of the story that follows Chet's death,[13] replacing it with 17 new pages. In this version, Chet's severed hand visits Josie's apartment at night and rolls up her window shade. As she is a vampire, the sunlight in the morning burns her to death while she sleeps, and she and Chet are reunited in the flames of Hell.[10]

Primary characters

[edit]- Ed

- A big-headed, childlike clown with Candide-like optimism, despite the hardships his creator puts him through.[6] He is a passive protagonist to and around whom events occur.[15] He spends much of the story with the head of a miniature Ronald Reagan from another dimension for a penishead. He later discovers, after having the president severed from his penis and having a new one attached, that he has a long-lost twin sister in Becky Backman. Brown considers Ed to be an "adult who's pre-adolescent",[12] whose sexuality is not fully formed.[12]

- Chet Doodley

- A janitor working at a hospital,[9] he is plagued with guilt over cheating on his wife[8] after his hand falls off for no apparent reason.[9] After having a dream in which a statue of the Virgin Mary turns into his girlfriend, Josie, and has sex with him, he murders Josie while having sex with her by stabbing her in the back in the woods. Josie, who becomes a vampire afterwards, hunts him down and eventually breaks his neck, sending him to Hell.[11] "Chet" is short for "Chester", and Douglas Wolk sees Chet as perhaps a stand-in for Brown himself,[9] though Brown denies any autobiographical elements in the story.[16] Brown has stated he had a phobia of losing his hand, as it would end his ability to draw, and so named the character "Chet".[17]

- Josie

- Chet's beautiful former girlfriend, who becomes a vampire "for actively engaging in a grievous sin"[13] for committing adultery with her boyfriend Chet, when he murders her by stabbing her in the back.[8] Her vampire self ends up saving Ed from having his penis decapitated by pygmy cannibals, and eventually tracks down Chet and kills him, sending him to Hell. In an alternate ending, she finds herself in Hell as well, eternally embracing Chet while being consumed by fire.[11]

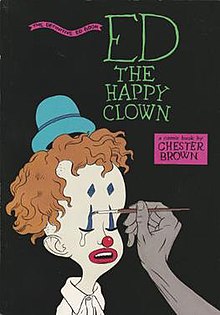

- Ronald Reagan

-

The Ronald Reagan character bears no resemblance to the actual president (pictured). Though bearing the American president's name and position, the diminutive Reagan bears no resemblance to his namesake.[18] He comes from Dimension X, and his head becomes attached to the end of Ed's penis after falling into an interdimensional portal. The president's body remains in Dimension X,[19] where people are much smaller than in Ed's, and are homosexual.[18]

Brown had intended to use Ed Broadbent, a left-wing politician of the Canadian New Democratic Party (NDP), but changed it to the right-wing Reagan as he believed Broadbent would have been too obscure to his American readers. He later regretted the decision and said he could have included an explanation.[17] The idea of a talking penis has appeared in a number of other comics, such as The Talking Head (1990) by Paolo Baciliero[20] and Pete Sickman-Garner's Young Tim.[21]

Analysis

[edit]Ed spans a range of Brown's interests, from political skepticism to scatological humour to vampires and werewolves. The story is dark and surreal, desperate and humorous.[6]

Christian elements especially—largely sacrilegious—are prominent in the book. They are at first innocuous and unimportant: a zombie named Christian, another character who believes he has found Christ's face on a piece of adhesive tape. With the fourth issue of Yummy Fur, Brown's surreal take on Christianity becomes central: the cover depicts the Virgin Mary holding not just the infant Christ, but also a severed hand. Within is the story of Saint Justin, whose amputation becomes a key motif: Chet loses his own hand and finds another; his own appears mysteriously under Ed's pillow. Only by praying for forgiveness for his adultery and by murdering his lover is Chet's hand miraculously restored. According to the Lives of the Saints,[16] the fictional[10] Saint Justin severed his own hand,[a] but in another version Brown presents, Justin's wife cuts it off with a woodaxe when she catches her husband masturbating after rejecting her advances.[16] Despite Saint Justin's story's exposure to the reader as a fraud, Chet's faith in the official version restores his severed hand.[22] The altered ending from 1992 has both Josie and Chet reunited in Hell, and the ghost of Chet's sister becomes a devil. As Brown mixes surreal sacrilege with the sort of moralism that compels him to condemn Josie for her bloody revenge, Brian Evenson calls Brown "deft at muddying the waters in a way that makes it very hard to pin him down as either belieever or satirist, as either anti-religionist or apologist".[16]

While not part of the Ed story, Brown had been serializing straight adaptations in Yummy Fur of the Gospels of Mark and of Matthew during most of Ed's run. R. Fiore called these adaptations "the best exploration of Christian mythology since Justin Green's Binky Brown",[23] comparing Chet's excessive Christian guilt with the "almost childlike retelling"[23] of Mark.[23] Yummy Fur readers also found "I Live in the Bottomless Pit", a short strip in which a man discovers the Antichrist, who after millennia underground has forgotten his mission—a paradoxical one, as he states his orders were from God.[16]

Ed prominently features transgressive content including nudity, graphic violence, racist imagery, blasphemy, and profanity. Brown grew up in a strictly Baptist household[24] in which he was not allowed to swear, as depicted in Brown's graphic novel I Never Liked You (1994).[25] Brown challenged his own anxieties by tackling subjects such as scatological humour.[b][26] Imagery such as the recurring Pygmy characters and their "ooga booga" language, Chris Lanier asserted, reinforce "old colonial imaging of 'third world natives'".[27]

Style

[edit]According to comics historian John Bell, "Brown arrived in print almost fully formed as an artist". His style, while showing the influence of artists such as Robert Crumb, Harold Gray, and Jack Kirby, was distinct from his predecessors. He continued to mature as an artist and draughtsman throughout the run of Ed,[8] showing enormous growth from the beginning to end of the graphic novel.[6]

Unlike most cartoonists, Brown does not compose his pages, but draws each panel on separate sheets of paper and assembles them into pages afterwards.[28] The panels in Ed were on 5-by-5-inch (13 cm × 13 cm)[12] squares of cheap typewriter paper, which he placed on a block of wood on his lap in lieu of a drawing board.[29] He used a number of different drawing tools, including Rapidograph technical pens, markers,[30] crowquill pens and ink brushes. He had some photocopies printed from his pencilled work, which he found both faster to produce and more spontaneous in feel.[12]

Brown worked freely, without ruling lines or lettering.[12] Usually he roughly sketched the artwork with a light blue pencil, then elaborated it with an HB pencil, at which stage he has said "most of the work [was] done".[12] Brown inked the pre-Vortex stories with a brush; when he committed himself to a regular schedule, he felt inking with a brush would be too slow, and switched to cheap markers or pencils to increase his productivity. He continued to use a brush to fill in blacks and to letter his dialogue balloons.[30] Brown came to favour the quality of the brush again toward the end of the story's run, but found it slow to work with and thus used it less than he would have preferred.[12] By photocopying before sending the artwork to the printer, Brown could ensure that the copy printed from was sufficiently black.[12]

While he occasionally scripted certain pages or scenes, more frequently he did not, and often wrote dialogue only after having drawn the artwork.[31] Brown did not plan out the stories, though he might have certain ideas prepared. Some ideas he found carried him for up to two to three issues of Yummy Fur. Brown used of flashback scenes different perspectives to alter the story to his needs—for example, when Brown revisited the scene of Josie's murder, he placed Ed behind a bush, linking the two characters' fates. When he had originally done the murder scene, he says he did not "know that Ed was over in the bushes a couple feet away".[26]

Brown found himself dissatisfied with much of the work, and later abandoning about a hundred printed pages which he intends not to have reprinted. He found that the improvisational method did not work well with Underwater in the 1990s; after cancelling that series he turned to carefully scripting out his stories, beginning with Louis Riel.[32]

Influences

[edit]When Brown started Ed, he was largely influenced by the comics he had grown up with, especially monster stories from Marvel Comics such as Werewolf by Night and Frankenstein's Monster by artists such as Mike Ploog, and from DC Comics such as Swamp Thing by artists such as Bernie Wrightson and Jim Aparo.[33]

Since graduating from high school, Brown had been inching towards underground comix, starting with the work of Richard Corben and especially Moebius in Heavy Metal, and eventually getting over his disgust over Robert Crumb's sex-laden comics to become a huge fan of the Zap and Weirdo artist.[34] He says the book that finally pulled him over into the underground was The Apex Treasury of Underground Comics, which included Crumb as well as Art Spiegelman's original short "Maus" story.[35] He was also affected by Will Eisner's graphic novel, A Contract with God.[2] Brown had already been an Eisner fan, but this book was different, "something that wasn't about a character with a mask on his face".[34] He started drawing in a more underground style, and submitting work to Raw, Last Gasp and Fantagraphics. The work was rejected from these publishers for one reason or another, and Brown was eventually convinced by his friend Kris Nakamura, who was active in the Toronto small press scene, to take it and self-publish it. His minicomic, Yummy Fur, was the result, and included the earliest instalments of the Ed the Happy Clown story.[36]

The book also drew inspiration from pulp science fiction, religious literature and television clichés.[8] Harold Gray's comic strip Little Orphan Annie had an effect on Brown after he discovered some Annie reprint books in the early 1980s. This was to be a primary influence on later work of Brown's such as Louis Riel.[34]

Publication

[edit]The story began in July 1983 in the second issue of Brown's original Yummy Fur minicomic, the seven issues of which were reprinted in 1986–87 in the first three issues of the Vortex Comics-published Yummy Fur. Ed ran in the first eighteen issues of Yummy Fur, along other features, such as Brown's Gospel adaptations.[37] Brown envisioned Ed as an ongoing character in the vein of Marvel and DC comic-book characters. In the late 1980s he came to feel restricted by the character;[38] inspired by the revealing autobiographical work of Julie Doucet and Joe Matt and the simple cartooning of fellow Toronto cartoonist Seth, Brown turned to autobiography.[39]

While Ed was the main feature of Yummy Fur until Brown switched to autobiographical comics in 1990, it was juxtaposed against straight adaptations of the gospels of Mark and Matthew, which filled up the rest of the Yummy Fur issues starting with issue #4.[40]

| # | Date | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | February | 2005 |

| 2 | May | |

| 3 | August | |

| 4 | November | |

| 5 | January | 2006 |

| 6 | March | |

| 7 | May | |

| 8 | July | |

| 9 | September | |

In 2004 Brown set to work on a revised Ed; he pencilled a number of pages, but stopped when he came to believe the new version was no better than the original.[7] Drawn & Quarterly—Brown's publisher since 1991—reissued the contents of the Definitive Ed collection in a nine issue series on smaller-sized pages from 2005 to 2006 titled Ed the Happy Clown, with new covers, previously unpublished art and extensive commentary by Brown.[7] The contents came mainly from issues two through twelve, and some from issue seventeen. About 80 pages—a third of the original Ed material—remains uncollected, including the entire 24-page ending that appeared in issue eighteen.[37]

The first collection, Ed the Happy Clown: A Yummy Fur Book, appeared in 1989 from Vortex Comics before Brown decided to end the story. It collects the Ed stories up to the twelfth issue of Yummy Fur and includes a cartoon foreword scripted by Harvey Pekar and drawn by Brown. It was this edition that in 1990 won Brown one of his two Harvey Awards, for Best Graphic Album,[41] and a UK Comic Art Award the same year for Best Graphic Novel/Collection.[42]

The second edition came from Vortex in 1992, after Brown had taken Yummy Fur to Drawn & Quarterly. Bill Marks had it labelled The Definitive Ed Book[13] for marketing reasons.[43] The edition reprinted what was in the first edition with an altered ending and some material from Yummy Fur #17, and excluded most of the material in the series from after Chet's death.[13]

In June 2012, Drawn & Quarterly published a third edition, Ed the Happy Clown: A Graphic-Novel, reprinting the contents of the Ed series of a few years earlier, including somewhat modified endnotes and annotations.[44] It had a new introduction by Brown,[45] replacing those by Pekar and Solomos in the previous editions. Compared to those editions, it was printed on higher-quality paper with higher contrast in the printing, and the artwork was reduced in size.[10] Brown subtitled the book with a hyphen: "graphic-novel". This reflects Brown's distaste yet reluctant acceptance of the term, as its usage had by then become widespread. Brian Evenson sees this as a Brown-like eccentricity and a gesture emphasizing the equal importance Brown places on both word and image.[28] The book was a bestseller.[46]

The 2012 edition also included a ten-page story called "The Door", which Brown redrew from an anonymous public domain story from a horror comic book. In the story, a couple go through a door in a funhouse which leads through a passage in which they get lost for years. Their clothes disintegrate over that time, exposing their genitals, until they finally come across another door—one that leads them to Hell. Brown wrote he found the original story truly horrifying, as the couple had done nothing apparent to deserve their fate. He had originally intended to incorporate it into the Ed story, but capriciously veered off in another narrative direction.[10]

| Date | Title | Publisher | Pages | ISBN | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Ed the Happy Clown: a Yummy Fur Book | Vortex | 198 | 978-0-921451-04-4 |

|

| 1992 | Ed the Happy Clown: the Definitive Ed Book | 215 | 978-0-921451-08-2 |

| |

| 2012 | Ed the Happy Clown: A Graphic Novel | Drawn & Quarterly | 240 | 978-1-77046-075-1 |

The artwork appeared at its largest in the Vortex Yummy Fur issues; it was somewhat smaller in the minicomics and first two collected editions. The artwork was smallest in the 2012 Drawn & Quarterly edition, a size Brown considered ideal, stating, "The smaller the better, as long as the words are still legible."[47] The 2012 edition also had wider page margins and gutters between the images.[47]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Ed was seen by many critics a high point of the early alternative comics scene in the 1980s, echoes of which can be seen in such later surrealistic graphics novels as Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron by Daniel Clowes and Black Hole by Charles Burns.[48] The story won praise from The Comics Journal[23] and mainstream publications such as The Village Voice[49] and Rolling Stone, which placed Ed on an early-1990s "Hot" list.[6] Time placed Ed at seventh on its list of "All Time Top Ten Graphic Novels",[50] while publisher and critic Kim Thompson placed Ed 27th on his top 100 comics of the 20th Century,[51] and editor and critic Tom Spurgeon called Ed "one of the three best alt-comix serials of all time".[52] The book appeared in Gene Kannenberg's 500 Essential Graphic Novels (2008).[53]

Ed had a large impact on a number of Brown's contemporaries, including fellow Canadians Dave Sim and Seth, the latter of whom was taken in by the ambitiousness of Brown's storytelling, saying "Those brilliant sequences where he would show a situation and then return to it later from a different perspective, like the death of Josie, really blew me away"[6]—and Dave Cooper, who called Ed "the most perfect book ever".[54] Others who cite Ed as an influence on their work include Daniel Clowes, Chris Ware, Craig Thompson, Matt Madden,[55] Eric Reynolds[56] and the Canadian cartoonists Alex Fellows, whose Canvas shows the influence of Ed, and Bryan Lee O'Malley, who calls Brown "a Golden God" and whose Lost at Sea was heavily influenced by Ed.[6] Anders Nilsen calls Ed "completely amazing and one of the best comics ever", placing it in his top five comic books,[57] and citing it as a major influence on his spontaneous Big Questions.[58]

Critic Chris Lanier placed Ed in a tradition that included Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, Max Andersson's Pixy, and Eric Drooker's Flood!;[59] he wrote that symbols appear with such frequency and importance in these works as to suggest significance, while remaining symbolically empty.[59] He finds predecessors for these works in German Dada[60] and the Theatre of the Absurd.[27] Reviewer Brad McKay found Ed "both hopeless and funny, a trick moviemakers like Tim Burton and Todd Solondz wish they could pull off more regularly".[6]

D. Aviva Rothschild likened the story to "staring at six-day-old roadkill".[20] Brown's father was too offended to keep reading after the fifth minicomic issue, "Ed and the Beanstalk".[17]

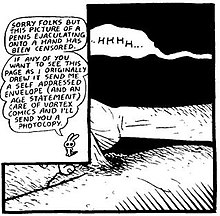

In Yummy Fur #4, there was a scene in which a fictional "Saint Justin" masturbates after putting off his wife's advances. In one panel "Saint Justin" had just ejaculated all over his hand, his penis in full view and his semen-covered hand clearly visible behind it. Vortex publisher Bill Marks had the panel covered up with another illustration after discussing it with Brown. Brown agreed to this censorship, but was "annoyed" by it. Marks later called it a mistake that he would not make again,[61] and when Brown included a scene in the following issue of the Ronald Reagan penishead vomiting Marks made no objection, and all future collections of Ed have the original uncensored panel.[62] The censored portion of the panel was covered with a note delivered by a rabbit that Brown often used as a surrogate self; the message read:

"Sorry folks but this picture of a penis ejaculating onto a hand has been censored. If any of you want to see this page as I originally drew it send me a self addressed envelope (and an age statement) care of Vortex Comics and I'll send you a photocopy."

Brown has said that perhaps 100 to 200 readers sent requests for the uncensored panel.[64]

In stores, Yummy Fur was often wrapped in plastic with "adults only" labels on it.[65] It is not known if Ed or Yummy Fur were banned from any stores, but Diamond, the largest American comics distributor, stopped carrying it for a time in 1988.[15] A publisher discovered that boxes of its feminist publication were lined with discarded pages of Yummy Fur, included pages in which Chet stabs Josie while having sex with her. The publisher lodged a complaint with the Ontario-based printer, which informed Vortex it would no longer handle Yummy Fur.[66] The third issue of the Drawn & Quarterly Ed series was seized at the Canadian border, but was later deemed admissible.[67]

Critic R. Fiore initially found the 1992 ending disappointing,[68] but changed his mind 2012, saying the sad ending gave Ed "an emotional punch that it wouldn't otherwise have".[11] Cartoonists such as Craig Thompson at first found the story off-putting, but later came to admire it.[6] Critic Douglas Wolk wrote that it is not surprising that Brown had not settled on one conclusion to the story, as that "would mean some kind of narrative closure", while Ed's premise is that "everything makes sense as a big picture eventually, but nothing can be relied on from moment to moment".[13]

In 2014, Uncivilized Books published Ed Vs. Yummy Fur Brian Evenson. The book details the differences between the various versions of the Ed narrative.[69]

Awards

[edit]| Year | Organization | Award | Notes | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Harvey Awards | Best Graphic Album[41] | For the first edition | Won |

| U.K. Comic Art Award | Best Graphic Novel/Collection[42] | For the first edition | Won | |

| 1999 | Urhunden Prizes | Foreign Album[70] | Won |

Other media

[edit]

Canadian filmmaker Bruce McDonald has had the rights since 1991[6] to adapt Ed to film, for which he has planned to use Yummy Fur as the title.[43] Such a film could use stop-motion animation,[71] but the project has yet to get off the ground.[72] At one point McDonald hoped to have Macaulay Culkin star as Ed, Rip Torn as Ronald Reagan and Drew Barrymore as Nancy Reagan. In 2000, it was reported that the movie would have a budget of $6,000,000,[73] but it was unable to get the financial backing. A script was written by Don McKellar,[6] and later with John Frizzell.[73]

In 2007, the City of Toronto government commissioned Brown to create six weeks' worth of new episodes of the strip as part of their Live with Culture campaign. The strips were published in Now magazine. In one episode a zombie and his human girlfriend attend a screening of McDonald's still-unmade adaptation of Ed.[74] The same year, McDonald placed Brown's graphic novel in scenes in his film The Tracey Fragments.[75]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mark 9:43; Brown quotes: "If thy hand offend thee, cut it off – it is better for thee to enter into life maimed than having two hands to go into hell."

- ^ At the time, Brown believed scatalogical humour was prevalent in Japanese comics, based on the few examples he had seen; he later learned it was much less so.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bell 2006, p. 144.

- ^ a b Juno 1997, p. 132.

- ^ Grace & Hoffman 2013, p. vii.

- ^ Køhlert 2012b, p. 378.

- ^ Juno 1997, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mackay 2005.

- ^ a b c d Wolk 2007, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d e Bell 2006, p. 154.

- ^ a b c d e f Wolk 2007, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Levin 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Fiore 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grammel 1990, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e f Wolk 2007, p. 150.

- ^ Levin 1993, p. 48.

- ^ a b Davis 1989.

- ^ a b c d e Evenson 2014, Chapter 2.

- ^ a b c Grammel 1990, p. 84.

- ^ a b Køhlert 2012a, p. 222.

- ^ Mackay 2005; Køhlert 2012a, p. 222.

- ^ a b Rothschild 1995, pp. 82, 91–92.

- ^ Wolk 1999.

- ^ Rodi 1988, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d Fiore 1987.

- ^ Hwang 1998; Juno 1997, p. 143.

- ^ Køhlert 2012, p. 379.

- ^ a b c Grammel 1990, p. 83.

- ^ a b Lanier 1995, p. 100.

- ^ a b Evenson 2014, "linkages".

- ^ Matt 1992.

- ^ a b Brown 2006, notes p. 1.

- ^ Grammel 1990, p. 86.

- ^ Epp 2002.

- ^ Grammel 1990, p. 85; Grammel 1990, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Grammel 1990, p. 77.

- ^ Grammel 1990, p. 78.

- ^ Grammel 1990, p. 79.

- ^ a b Evenson 2014, Chapter 3.

- ^ Levin 1993, p. 47.

- ^ Køhlert 2012b, p. 381.

- ^ Pustz 1999, p. 92.

- ^ a b Harvey Awards staff 1990.

- ^ a b Bell 2006, p. 150.

- ^ a b Arnold 2004.

- ^ Levin 2012; Carlick 2012.

- ^ Blake 2012.

- ^ New York Times staff 2012.

- ^ a b Evenson 2014, Chapter 4.

- ^ Køhlert 2012a, p. 224.

- ^ Mackay 2005; Bell 2006, p. 150.

- ^ Arnold 2005; Rhoades 2008, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Thompson 2002.

- ^ Spurgeon 2005.

- ^ Kannenberg 2008.

- ^ McKeown 2002.

- ^ Nester 2005; Carlick 2012.

- ^ Contino & Atchison 2002.

- ^ Algeo 2011.

- ^ Romberger 2011.

- ^ a b Lanier 1995, p. 99.

- ^ Lanier 1995, p. 102.

- ^ Grammel 1990, p. 88.

- ^ Brown 2006, notes p. 2.

- ^ Brown 1987, p. 3, panel 3; Evenson 2014, Chapter 4.

- ^ Evenson 2014, Chapter 4; Appendix: Interview with Chester Brown.

- ^ Mackay 2005; Grammel 1990, p. 88.

- ^ Mackay 2005; Brown 2006, notes p. 1.

- ^ Comic Book Legal Defense Fund staff 2011, p. 23.

- ^ Fiore 1992, p. 42.

- ^ Hunter 2014.

- ^ Hammarlund 2007; Hahn 2006.

- ^ Halfyard 2007.

- ^ Guillen 2007.

- ^ a b Playback staff 2000.

- ^ Rogers 2008.

- ^ Verniere 2008.

Works cited

[edit]Books

[edit]- Bell, John (2006). Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-659-7.

- Evenson, Brian (2014). Ed Vs. Yummy Fur. Uncivilized Books. ISBN 978-0-9889014-2-1.

- Juno, Andrea (1997). "Interview with Chester Brown". Dangerous Drawings. Juno Books, LLC. pp. 130–147. ISBN 0-9651042-8-1.

- Kannenberg, Gene (2008). 500 Essential Graphic Novels: The Ultimate Guide. ILEX. ISBN 9781905814299. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- Køhlert, Frederik Byrn (2012). "I Never Liked You: A Comic-Strip Narrative". In Beaty, Bart H.; Weiner, Stephen (eds.). Critical Survey of Graphic Novels: Independent and Underground Classics. Salem Press. pp. 378–381. ISBN 978-1-58765-950-8.

- Matt, Joe (1992). "Nov. 27th, 1990". Peepshow. Kitchen Sink Press. p. 68. ISBN 1-896597-27-0.

- Pustz, Matthew J. (1999). Comic Book Culture: Fanboys and True Believers. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-201-0.

- Rhoades, Shirrel (2008). Comic Books: How the Industry Works. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-8892-9.

- Rothschild, D. Aviva (1995). Graphic Novels: A Bibliographic Guide to Book-length Comics. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 978-1-56308-086-9.

- Wolk, Douglas (2007). "Chester Brown: The Outsider". Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean. Da Capo Press. pp. 147–155. ISBN 978-0-306-81509-6.

Journals and magazines

[edit]- Brown, Chester (April 1987). Yummy Fur. Vortex Comics.

- Brown, Chester (January 2006). Ed the Happy Clown. Drawn & Quarterly.

- Davis, Erik (January 1989). "Ed's Big Boy". Spin. 4 (10): 13. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- Fiore, Richard (December 1987). "Review of Yummy Fur #4–5". The Comics Journal (118). Fantagraphics Books: 45–46. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Fiore, Richard (May 1992). "Funnybook Roulette". The Comics Journal (150). Fantagraphics Books: 41–43. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Grace, Dominick; Hoffman, Eric (2013). "Introduction". In Grace, Dominick; Hoffman, Eric (eds.). Chester Brown: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. vii–xxxi. ISBN 978-1-61703-868-6.

- Grammel, Scott (April 1990). "Chester Brown (interview)". The Comics Journal (135). Fantagraphics Books: 66–90. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Køhlert, Frederik Byrn (2012a). "Ed the Happy Clown: The Definitive Ed Book". In Beaty, Bart H.; Weiner, Stephen (eds.). Critical Survey of Graphic Novels: Independent and Underground Classics. Salem Press. pp. 221–224. ISBN 978-1-58765-950-8.

- Køhlert, Frederik Byrn (2012b). "I Never Liked You: A Comic-Strip Narrative". In Beaty, Bart H.; Weiner, Stephen (eds.). Critical Survey of Graphic Novels: Independent and Underground Classics. Salem Press. pp. 378–381. ISBN 978-1-58765-950-8.

- Lanier, Chris (February 1995). "Pixy and the Post-Nuke Protagonist". The Comics Journal (174). Fantagraphics Books: 96–102. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Levin, Bob (October 1993). "Chester Brown". The Comics Journal (162). Fantagraphics Books: 45–49. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Levin, Bob (2012-07-09). "To Hell and Back". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- McKeown, Patrick (August 2002). "The Dave Cooper Interview". The Comics Journal (245). Fantagraphics Books: 76–106. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Rogers, Sean (2008-09-22). "Chester Brown's Zombie Romance". The Walrus. Archived from the original on 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- Wolk, Douglas (October 1999). "Lightreading: Greasy Kids Stuff". CMJ. 74: 68. ISSN 1074-6978.

Other sources

[edit]- Algeo, Courtney (2011-11-02). "Anders Nilsen, creator of cartoons both terrifying and meaningful". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- Arnold, Andrew D. (2004-04-12). "Keeping it 'Riel'". Time. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- Arnold, Andrew D. (2005-10-16). "Ed the Happy Clown (1989), by Chester Brown". Time. Archived from the original on 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- Blake, Cory (2012-06-06). "3 New Comics for New Readers – June 6, 2012". Comics Observer. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Carlick, Stephen (2012-06-26). "Welcome Back, Ed the Happy Clown". Maclean's. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- Comic Book Legal Defense Fund staff (2011). "Comics Seized by Canadian Border Officials from 2003–2010" (DOC). Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- Contino, Jennifer M.; Atchison, Lee (December 2002). "Fantagraphics Man of Many Hats: Eric Reynolds". Sequential Tart. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- Brown, Chester. Ed the Happy Clown. Drawn & Quarterly. Nine issues (February 2005 – September 2006)

(notes pages unnumbered; pages counted from first page of notes) - Epp, Darell (2002-01-29). "Two-Handed Man interviews cartoonist Chester Brown". twohandedman.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- Fiore, R. (2012-06-27). "Gold Out of Straw". The Comics Journal. Archived from the original on 2012-06-30. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- Guillen, Michael (2007-12-01). "Madame Tutli-Putli—Interview With Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski". Twitch Film. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- Hahn, Joel (2006). "Urhunden Prize". Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- Halfyard, Kurt (2007-09-15). "Ed the Happy Clown Adaptation in the Works. Stop Motion by the Madame Tutli-Putli folks?". Twitch Film. Archived from the original on 2011-12-09. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- Hunter, Greg (2014-08-13). "'What's Actually There on the Page': A Conversation with Brian Evenson about Chester Brown". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on 2014-08-20. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- Hammarlund, Ova (2007-08-08). "Urhunden: Satir och iransk kvinnoskildring får seriepris" (in Swedish). Urhunden. Archived from the original on 2019-04-13. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- Harvey Awards staff (1990). "1990 Harvey Award Winners". Harvey Awards. Archived from the original on 2013-11-08. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- Hwang, Francis (1998-12-23). "Graven Images". City Pages. Archived from the original on 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- Mackay, Brad (2005-07-18). "Special Ed". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- Nester, Daniel (October 2005). "An Interview with Matt Madden". Bookslut. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- New York Times staff (2012-06-19). "Bestsellers: Hardcover Graphic Books: June 24, 2012". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-10-12. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- Playback staff (2000-06-12). "McDonald goes hard core with sex, violence". Playback Online. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- Rodi, Rob (July 1988). "The Dead and the Living". The Comics Journal (123). Fantagraphics Books: 41–44. ISSN 0194-7869.

- Romberger, James (2011-08-09). "Massive, Eccentric, Ambitious: Anders Nilsen's 'Big Questions'". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- Spurgeon, Tom (2005-08-24). "Eight Stories for '05 #4 -- The Return of Alt-Comix?". The Comics Reporter. Archived from the original on 2005-12-02. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- Thompson, Kim (2002). "Kim Thompson's Top 100". Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- Verniere, James (2008-06-27). "'Fragments' Takes Page out of 'Juno'". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on 2015-02-02. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

External links

[edit]- Ed the Happy Clown character at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Ed the Happy Clown TPB (first edition, 1989) at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Ed the Happy Clown: the Definitive Edition (1992) at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Ed the Happy Clown (Drawn & Quarterly series) at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Ed the Happy Clown (Drawn & Quarterly series) at the Grand Comics Database

- Comics publications

- 1983 comics debuts

- 2006 comics endings

- Comics characters

- Drawn & Quarterly titles

- Harvey Award winners for Best Graphic Album

- Books by Chester Brown

- Comics by Chester Brown

- 1989 graphic novels

- 1992 graphic novels

- 2012 graphic novels

- Obscenity controversies in comics

- Canadian comics characters

- Fictional clowns

- Fictional Canadian people

- Cultural depictions of Ronald Reagan